On finishing our lunch in the Plaza de Bib-Rambla, we consulted our map to find the best way

to reach the cathedral, as we wanted

to do something with the remainder of the day, and knew

that the cathedral was nearby. There seemed to be a more direct route to the cathedral than

the way from which we'd approached the plaza. This improved route consisted of a short block

to the north, which led to the Plaza de las Pasiegas. This plaza seemed to open in front of

the foot of the cathedral, which would normally be the cathedral's main façade. We investigated

and found all of this to be correct, and were confronted with the cathedral's imposing façade.

Cathedral Façade and Bell Tower

Cathedral Façade

Façade and Bell Tower

One thing we were not confronted with was an entrance. All three of the façade's doors were

closed, and a sturdy fence barred any approach to them. It seemed too early for the cathedral

to be closed, so we made our way around the cathedral in search of the tourist entrance,

proceeding in a counter-clockwise direction. This took us back up the street which we'd used

to reach the Plaza de Bib-Rambla, a street called Calle Oficios. Part way up Oficios we found

the Capilla Real, or Royal Chapel

(we'd passed it earlier, but were driven by hunger to not be too curious).

Entrance to Royal Chapel

Bob Outside Royal Chapel

Above Main Door to Royal Chapel

Royal Chapel Stonework

We knew some things about the Royal Chapel from the guidebooks. For one, the chapel was connected

to the cathedral but was a separate admission, with the door between them being kept closed and

locked. For the rest, we'll have to return our attentions to the eventful year 1492.

After conquering the last Moorish kingdom in Spain, forcing all the Jews in Spain to convert or

clear out, and sending Christopher Columbus off to prepare for his lunatic trip westward to the

Indies, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand didn't hang around in Granada too much longer. In the

early days of a united Spain there was no official Spanish capital city (Ferdinand and Isabella's

great-grandson Philip II wouldn't establish Madrid as the capital until 1561), so Ferdinand and

Isabella were itinerant monarchs, moving around from city to city in their kingdom to keep track

of what was going on. During this time they were busy strategically marrying off their five adult

children. For instance, their youngest daughter, Catherine, was married to Arthur, England's

Prince of Wales (this didn't work out well, as Arthur died within a year of the wedding; Catherine

later married his younger brother, who became King Henry VIII; Catherine is commonly called

Catherine of Aragon). Another daughter, Joanna, married Philip the Handsome, a member of the

Habsburg dynasty. Philip was the son of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (Philip didn't live long

enough to inherit the throne, but Joanna and Philip's son, Charles, would inherit the thrones of

both the Spanish Empire, including its New World possessions, and the Holy Roman Empire).

Around 1497, Isabella's health started to fail, coincidentally with the beginning of a series of

tragedies involving her children. First, her eldest son John died in 1497 shortly after marrying

an Austrian Archduchess. Next, her eldest daughter, also named Isabella, died in childbirth in

1498 after marrying Manuel I of Portugal (the child, a son named Miguel, was to die at the age of

two). Third, her daughter Catherine's husband, the Prince of Wales, died in 1502, leaving

uncertainty about Catherine's future (she wasn't to marry Henry until 1509). And fourth, her

daughter Joanna, now the heir to the Castilian throne, was apparently showing signs of mental

illness. Isabella was to eventually die on November 26, 1504, at the age of 53, in Valladolid,

where she and Ferdinand had married in 1469. Before this happened, though, she agreed with

Ferdinand that they would be buried together in Granada, and together they commissioned the

construction of a Royal Chapel to be used for this purpose.

On Isabella's death, Ferdinand was not ready to be buried just yet, nor was the Royal Chapel

completed (or even begun – work began in 1505), so Isabella was buried, alone and temporarily, in

a Franciscan convent that had been established at the Alhambra. Also on Isabella's death,

Ferdinand ceased being King of Castile, with the monarchs' eldest surviving daughter succeeding

to the throne as Joanna I (Ferdinand remained King of Aragon, which was no longer a united entity

with Castile). The next couple of years were stormy, with Joanna's husband Philip (who was

co-ruling as Philip I) dying in 1506. After this time, Joanna was judged to be mentally unstable,

and Ferdinand was brought in to rule Castile as regent (Joanna, later known as Joanna the Mad, was

confined to a nunnery, and her son Charles was only six years old and not yet ready to rule).

Ferdinand looked with disfavor on Philip and Charles, as they both had creepy Habsburg blood in

them, and he remarried a niece of Louis XII of France in an unsuccessful attempt to produce an

alternate heir. When Ferdinand died in 1516, Charles became ruler (or technically co-ruler with

his mother, who remained in the nunnery until her death in 1555) of both Castile and Aragon, to

which the title Holy Roman Emperor was added in 1519, on the death of Maximilian I.

When Ferdinand died in 1516, work on the Royal Chapel had proceeded apace, but the structure was

still not quite finished. Ferdinand was buried with Isabella at the Alhambra to await the chapel's

completion. Charles, apparently conscious of his heritage, made sure the chapel was finished,

which took place in 1517, and had his grandparents moved to its crypt in 1521. He also devoted

considerable attention to the chapel's decoration over the next several years.

The Royal Chapel was built in a style called Isabel, an odd combination of gothic and flamboyant.

It's a church in itself, but with only one side exposed to the elements – other structures,

including the cathedral, grew up around it following its completion. It's elaborately decorated

inside, with a large main altarpiece, other smaller altarpieces, a huge main grille separating the

tombs and main altarpiece from the rest of the chapel, and a considerable amount of artwork.

Spanish, Flemish and Italian artists (such as Botticelli, Perugino, Van der Weyden, Bouts and

Memling) are represented. A number of artifacts are on display, including Isabella's crown and

sceptre and Ferdinand's sword. There are two beautifully carved marble tombs, one for Ferdinand

and Isabella and one for Joanna and Philip (subsequent Spanish monarchs, starting with Charles,

are buried in El Escorial,

near Madrid). The tombs, however, are empty. The remains of all four

monarchs are found in a low-ceilinged, simple crypt below the tombs, in simple leaden coffins on

unadorned stone platforms. A small fifth coffin can also be seen here, belonging to Miguel, the

grandson who had only lived to the age of two (and who could have united the kingdoms of Portugal

and Spain if he had lived to adulthood).

Lighting in the Royal Chapel is dim, and photography is forbidden anyway, so our pictures came out

quite poorly. But some of the pictures don't look too horrible if they're kept tiny, so a collage

has been supplied below for your edification. If you would like to see better pictures, you might

consider the chapel's website.

Royal Chapel Collage

From the Royal Chapel we resumed our circumnavigation of the cathedral, looking for an entrance,

and we eventually found one, through a gate along the area's main boulevard, Calle Gran Vía de

Colón.

Cathedral from Nearby Street

Cathedral Dome

Bob at the Gate

Planning work on the cathedral began

around the same time as work on the Royal Chapel, but

the Royal Chapel was given precedence, so the first stone for the cathedral wasn't actually

laid until 1523. It was begun as a gothic structure, to be situated on the former site of

the city's main mosque. But plans had to be changed after a 1526 visit by King/Emperor Charles,

who envisioned the cathedral's main dome as the pantheon for burial of the future Spanish

Habsburgs. Also, gothic architecture was going out of fashion at the time, so a more modern

Renaissance architecture was recommended. When the king/emperor recommends something, it is

unwise to say "No, I don’t think so", so when the original architect, Enrique Egas, seemed

unable to implement the needed updates, he was dismissed and replaced with a new architect,

Diego de Siloe. Siloe was the chief architect from 1526 until his death in 1563, and the

eventual finished design is primarily his.

The design is somewhat unusual, in that the main chapel is circular and directly under the

dome, rather than under a semicircular apse as was more typical. Niches were designed into

the chapel wall supporting the dome, to house the remains of future monarchs (these remain

empty, as Charles's son Philip II rerouted all such remains, including those of Charles and

himself, to El Escorial).

Also, the floor plan doesn't have the customary cross shape, as the

cathedral has five naves and is thus mainly rectangular (though the central nave and the

transept can be seen as forming a Latin cross).

Wooden Model of Cathedral

The architects that succeeded Siloe pretty much stuck to his design (though with a few deviations),

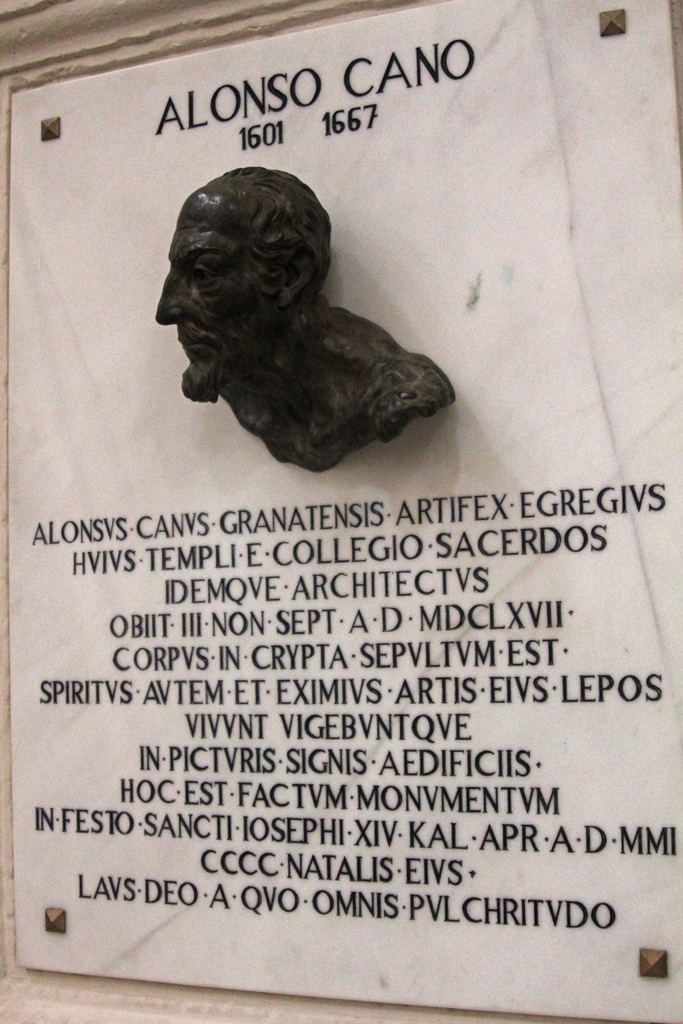

but in 1667, Alonso Cano (who worked on the project for a total of 123 days before dying) added

some baroque touches, mainly to the cathedral's façade. The cathedral was finally finished in 1704.

Alonso Cano Plaque

The entry to the cathedral pointed us directly into the main chapel, where we had a nice

view of the dome and the main altar (which was a little domed structure of its own).

Inside the Dome

Main Chapel

Main Chapel

Main Altar with Statuary

Top of Pulpit (added in 1714)

Like most cathedrals, this one has many chapels (some small, some less so) lining its outer walls.

Chapel of St. Jacob (1640)

Capilla Jesús Nazareno

Capilla San Miguel

Lactación de San Bernardo, Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra

Capilla Virgen de las Angustias (1737-41)

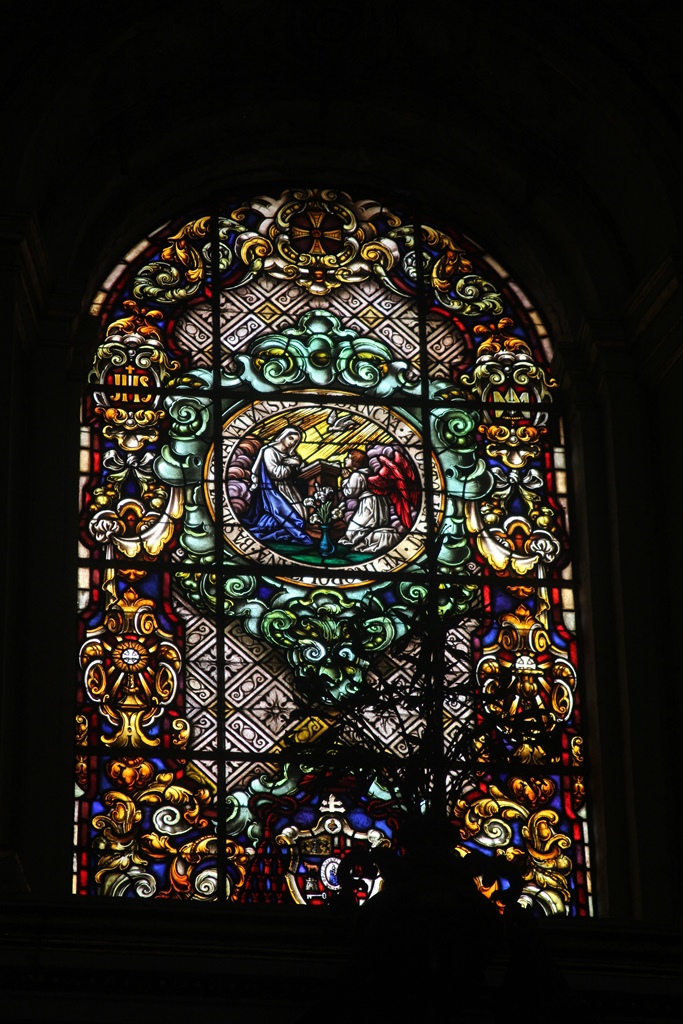

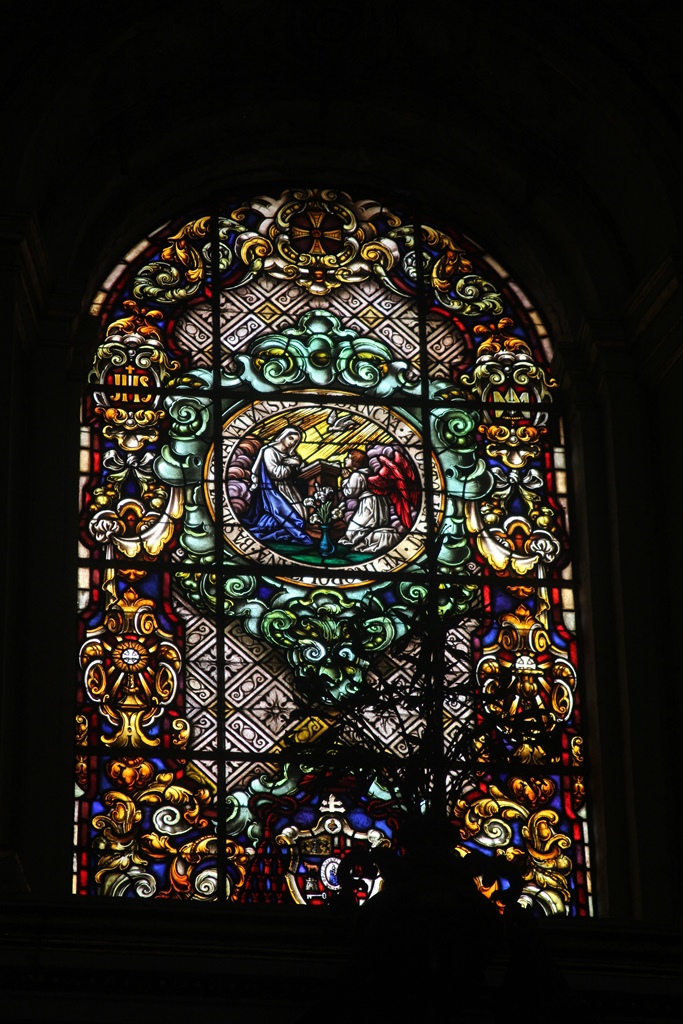

Window Above Capilla Virgen de las Angustias

Capilla Virgen de la Antigua

Capilla Virgen de la Antigua (detail)

Capilla Santa Lucía

During our exploration of the cathedral, we came across the elaborate (and locked) doorway to the Royal Chapel.

Door to Capilla Real

There were a few over-the-top church organs, dating from the 18th Century.

Organ

Organ

Side Nave

Nella with Audioguide

After having our fill of the cathedral, we returned to the hotel room to rest a little, and

after dark we ventured out to find dinner, again landing in Plaza de Bib-Rambla.

Philip with Tapas

Philip's Tapas

Bowl of Breadcrumbs

Seafood

After dinner we returned pretty directly to the hotel to get some sleep, after this long day

which had begun in Madrid. The next day would be our one full day in Granada, and we would

be starting it with a morning appointment at the Alhambra.